|

Оценить:

|

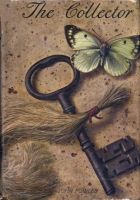

The Collector

- Предыдущая

- 39/47

- Следующая

39

Otherwise I was afraid I would fall into the old trap of pitying him.

So I was a bit nicer at supper-time and said I needed a bath (which I did). He went away, came back, we went up. And there, it seemed a sign, specially left for me, was a small axe. It was on the kitchen window-sill, which is next to the door. He must have been chopping wood outside and forgotten to hide it. My always being down here.

We passed indoors too quickly for me to do anything then.

But I lay in the bath and thought. I decided it must be done. I had to catch up the axe and hit him with the blunt end, knock him out. I hadn’t the least idea where on the head was the best place to hit or how hard it had to be.

Then I asked to go straight back. As we went out through the kitchen door, I dropped my talcum powder and things and stood to one side, towards the window-sill, as if I was looking to see where they’d gone. He did just what I wanted and bent forward to pick them up. I wasn’t nervous, I picked the axe up very neatly, I didn’t scrape the blade and it was the blunt end. But then… it was like waking up out of a bad dream. I had to hit him and I couldn’t but I had to.

Then he began to straighten up (all this happened in a flash, really) and I did hit him. But he was turning and I didn’t hit straight. Or hard enough. I mean, I lashed out in a panic at the last moment. He fell sideways, but I knew he wasn’t knocked out, he still kept hold of me, I suddenly felt I had to kill him or he would kill me. I hit him again, but he had his arm up, at the same time he kicked out and knocked me off my feet.

It was too horrible. Panting, straining, like animals. Then suddenly I knew it was — I don’t know, undignified. It sounds absurd, but that was it. Like a statue lying on its side. Like a fat woman trying to get up off the grass.

We got up, he pushed me roughly towards the door, keeping a tight hold of me. But that was all. I had a funny feeling it was the same for him — disgusting.

I thought someone may have heard, even though I couldn’t call out. But it was windy. Wet and cold. No one would have been out.

I’ve been lying on the bed. I soon stopped crying. I’ve been lying for hours in the dark and thinking.

November 22

I am ashamed. I let myself down vilely.

I’ve come to a series of decisions. Thoughts.

Violence and force are wrong. If I use violence I descend to his level. It means that I have no real belief in the power of reason, and sympathy and humanity. That I lameduck people only because it flatters me, not because I believe they need my sympathy. I’ve been thinking back to Ladymont, to people I lameducked there. Sally Margison. I lameducked her just to show the Vestal Virgins that I was cleverer than they. That I could get her to do things for me that she wouldn’t do for them. Donald and Piers (because I’ve lameducked him in a sense, too) — but they’re both attractive young men. There were probably hundreds of other people who needed lameducking, my sympathy, far more than those two. And anyway, most girls would have jumped at the chance of lameducking them.

I’ve given up too soon with Caliban. I’ve got to take up a new attitude with him. The prisoner-warder idea was silly. I won’t spit at him any more. I’ll be silent when he irritates me. I’ll treat him as someone who needs all my sympathy and understanding. I’ll go on trying to teach him things about art. Other things.

There’s only one way to do things. The right way. Not what they meant by “the Right Way” at Ladymont. But the way you feel is right. My own right way.

I am a moral person. I am not ashamed of being moral. I will not let Caliban make me immoral; even though he deserves all my hatred and bitterness and an axe in his head.

(Later.) I’ve been nice to him. That is, not the cat I’ve been lately. As soon as he came in I made him let me look at his head, and I dabbed some Dettol on it. He was nervous. I make him jumpy. He doesn’t trust me. That is precisely the state I shouldn’t have got him into.

It’s difficult, though. When I’m being beastly to him, he has such a way of looking sorry for himself that I begin to hate myself. But as soon as I begin to be nice to him, a sort of self-satisfaction seems to creep into his voice and his manner (very discreet, he’s been humility itself all day, no reproach about last night, of course) and I begin to want to goad and slap him again.

A tightrope.

But it’s cleared the air.

(Night.) I tried to teach him what to look for in abstract art after supper. It’s hopeless. He has it fixed in his poor dim noddle that art is fiddling away (he can’t understand why I don’t “rub out”) until you get an exact photographic likeness and that making lovely cool designs (Ben Nicholson) is vaguely immoral. I can see it makes a nice pattern, he said. But he won’t concede that “making a nice pattern” is art. With him, it’s that certain words have terribly strong undertones. Everything to do with art embarrasses him (and I suppose fascinates him). It’s all vaguely immoral. He knows great art is great, but “great” means locked away in museums and spoken about when you want to show off. Living art, modern art shocks him. You can’t talk about it with him because the word “art” starts off a whole series of shocked, guilty ideas in him.

I wish I knew if there were many people like him. Of course I know the vast majority — especially the New People — don’t care a damn about any of the arts. But is it because they are like him? Or because they just couldn’t care less? I mean, does it really bore them (so that they don’t need it at all in their lives) or does it secretly shock and dismay them, so that they have to pretend to be bored?

November 23

I’ve just finished Saturday Night and Sunday Morning. It’s shocked me. It’s shocked me in itself and it’s shocked me be-cause of where I am.

It shocked me in the same way as Room at the Top shocked me when I read it last year. I know they’re very clever, it must be wonderful to be able to write like Alan Sillitoe. Real, unphoney. Saying what you mean. If he was a painter it would be wonderful (he’d be like John Bratby, much better) he’d be able to set Nottingham down and it would be wonderful in paint. Because he painted so well, put down what he saw, people would admire him. But it isn’t enough to write well (I mean choose the right words and so on) to be a good writer. Because I think Saturday Night and Sunday Morning is disgusting. I think Arthur Seaton is disgusting. And I think the most disgusting thing of all is that Alan Sillitoe doesn’t show that he’s disgusted by his young man. I think they think young men like that are really rather fine.

I hated the way Arthur Seaton just doesn’t care about anything outside his own little life. He’s mean, narrow, selfish, brutal. Because he’s cheeky and hates his work and is successful with women, he’s supposed to be vital.

The only thing I like about him is the feeling that there is something there that could be used for good if it could be got at.

It’s the inwardness of such people. Their not caring what happens anywhere else in the world. In life.

Their being-in-a-box.

Perhaps Alan Sillitoe wanted to attack the society that produces such people. But he doesn’t make it clear. I know what he’s done, he’s fallen in love with what he’s painting. He started out to paint it as ugly as it is, but then its ugliness conquered him, and he started trying to cheat. To prettify.

It shocked me too because of Caliban. I see there’s something of Arthur Seaton in him, only in him it’s turned upside down. I mean, he has that hate of other things and other people outside his own type. He has that selfishness — it’s not even an honest selfishness, because he puts the blame on life and then enjoys being selfish with a free conscience. He’s obstinate, too.

This has shocked me because I think everyone now except us (and we’re contaminated) has this selfishness and this’ brutality, whether it’s hidden, mousy, and perverse, or obvious and crude. Religion’s as good as dead, there’s nothing to hold back the New People, they’ll grow stronger and stronger and swamp us.

No, they won’t. Because of David. Because of people like Alan Sillitoe (it says on the back he was the son of a labourer). I mean the intelligent New People will always revolt and come across to our side. The New People destroy themselves because they’re so stupid. They can never keep the intelligent ones with them. Especially the young ones. We want something better than just money and keeping up with the Joneses.

But it’s a battle. It’s like being in a city and being besieged. They’re all around. And we’ve got to hold out.

It’s a battle between Caliban and myself. He is the New People and I am the Few.

I must fight with my weapons. Not his. Not selfishness and brutality and shame and resentment.

He’s worse than the Arthur Seaton kind.

If Arthur Seaton saw a modern statue he didn’t like, he’d smash it. But Caliban would drape a tarpaulin round it. I don’t know which is worse. But I think Caliban’s way is.

November 24

I’m getting desperate to escape. I can’t get any relief from drawing or playing records or reading. The burning burning need I have (all prisoners must have) is for other people. Caliban is only half a person at the best of times. I want to see dozens and dozens of strange faces. Like being terribly thirsty and gulping down glass after glass of water. Exactly like that. I read once that nobody can stand more than ten years in prison, or more than one year of solitary confinement.

- Предыдущая

- 39/47

- Следующая